|

Connections

By James A. Johnston

For a short time, all too short, my wife Pam and I spent a delightful hour and a half at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. We had broken away from a conference I was attending during the noon break and were able to make it to the museum via the "Boston T" in a matter of minutes. I had to be back at the conference at two o'clock, so the visit was going to have to be quick. Usually, when I visit an art museum like the MFA, I plan on spending the better part of a day, but not today. This was the only opportunity that we had to visit this museum, and we had to make the most of it.

Upon entering and receiving the guide brochure, we orientated ourselves. The building is very large with about 40 galleries on two levels, and scanning the brochure told us that most of the contemporary art, including the impressionism pieces, were upstairs. After first visiting a first floor gallery, off the rotunda, where a large white orchard painted by Georgia O'Keeffe beckoned to us through the glass doors, and spending a few minutes viewing contemporary American pieces, we made our way to the elevators.

We left the elevator at the second floor, and veering left for a few steps, we were at the Impressionist and Post Impressionist Gallery. While the room wasn't extremely large, in comparison to some other galleries, it has one of the most extensive exhibits of Monet's pieces, about twelve as I

recall in any one location. I had missed the traveling Monet exhibit when it had been at the Chicago Art Institute, a few years back, so at least now my conscience was a bit eased when finally I got to see so many of them in one location. There were other works on display here, including Van Gogh among others, but on this day it was the Monets that held my attention, undoubtedly because there were so many of them.

As we made our way around the room I was customarily first viewing from a distance, and then moving closer to take in the details. When I'm moving in closer I change my eyeglasses from bifocals, to the "readers" (glasses with just the reading lenses specially made so that I don't have to crane my neck when sitting in front of a computer monitor). And even with special glasses I'm so nearsighted, that in order to see things really close up, I have to take off my glasses and get right next to an object.

It was this process that I was going through with all the pieces in the room, looking first at from a distance, then moving in and viewing through the reading glasses, and finally viewing sans glasses altogether. When I looked really close up, I could make out how Monet did it. Layers of pure color overlaid one on top of another. His violets were created with strokes of red overlaid with strokes of blue. His brush strokes were small, so that when your eye caught the red and blue together, the overall effect was violet.

There were about fifteen people in this gallery at this time, and as we moved around from piece to piece, and I was doing my glasses and moving closer ritual, I

accidentally bumped into an older gentleman, and we simultaneously said "excuse me" to each other. He was experiencing the same piece that I was, and moving in for a closer look. The piece we were both looking at was "The Old Fort at Atibes," which is a building on a overlook of seaside, and pictured from the water. Both of us were so obviously engrossed in the piece, that we failed to see each other.

We only spent about 15 minutes or so here, but I did manage to go back to see a couple of pieces that I did want to take in again, including "The Old Fort at Atibes," I noticed the same older gentleman still standing in front of the painting, obviously enraptured by it.

But time was beginning to become a factor and Pam and I had to move on. We left the impressionism gallery and after taking in the featured exhibit of Edward Weston, "Photography and Modernism" on the same floor, we had just about used up the hour and half we had allotted for this visit. So we hurried back to the elevators, passing the impressionism galley on the way. As we walked by, I glanced in and saw the same older man that I had bumped into some thirty minutes earlier still glued to the "The Old Fort at Atibes". In fact this time he was rising from the bench seat directly in front of the piece and with eyes totally fixed on the painting, was making his way for another closer look. There was a serene smile on his face, which was another indication of the joy that his soul was

experiencing. Then I realized exactly what was happening. The man was completely mesmerized by the piece. He and Monet were actively engaged in that mysterious and wonderful silent communication that can exist between an artist and a viewer. Although the artist had been physically dead for almost 100 years, he was still communicating through his creation. The beauty communicated by Monet was still as alive as it was the day he had finished the piece in 1879. Monet and this gentleman spectator had established a bond. The artist's spirit was communicating in the manner that only art, in its purest sense, has the potential to do.

Observing this person's enrapture with Monet's piece then brought to mind a concept that I had been trying to grasp for a number of years ever since I had started painting and taken up the creative process to make visual art again. That concept is the ability of an artistic piece to

intangibly communicate with the inner souls of the observer/viewers, the people who are experiencing the work. It is the ability of art to touch the emotional reality of one's soul that is so fascinating and mystical to me.

We've all been uplifted by art, it's part of the human experience. The forms are many: the performing arts: music, dance, theater etc; the literary: poetry, drama, novels, short stories etc; the visual; painting and prints, drawings, and sculpture. Certainly every one of us has experienced emotional uplifting (or in some cases just the opposite) from these forms of human expression. To some it may be a catharsis, or an experience of emotional release which the art has inspired. To others it may just be the good feeling that comes when on sees or hears beauty represented in art.

I became aware of this phenomena in a very personal way during the runs of my own art which is contained in an exhibit called ‘The Garden of Humanity'. I've noticed this effect several times, as have others, when observing the reactions of people viewing the pieces on display. While most viewers will generally stop to experience a piece for a few minutes or so, there are those that will become engrossed by a particular piece and might stand in front of it a long period of time, even to the extent of the older gentlemen I bumped into in front of the Monet piece as described previously.

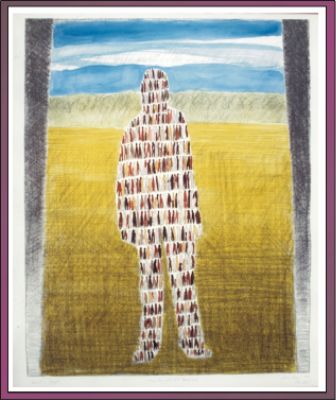

One such occurrence was at the reception held at the Prairie Art Alliance, the art co-op that I belong to, in my home town of Springfield Illinois. For one month, my work was featured as the "Artist of the Month" and the pieces were displayed in a special gallery room reserved for the featured artists. The opening reception was held on a Saturday evening, with about 100 in attendance. As the many spectators streamed by to view my work following a short "gallery talk" I had a chance to talk and shake hands with many people. As the night progressed, I noticed a certain man returning at least three times to take in the lithograph, "The Oneness of Mankind". Not only was he engrossed with the piece, but it was very evident that he was really studying the little placard next to it that contained Baha'u'llah's famous Hidden Word that begins "O Children of Men, Know not why We created you from the same dust,...".

I thought of approaching this viewer but then realized that the communication that I meant to achieve had been fulfilled. The piece's message had been received, and whatever happened henceforth would be up to his, the viewer's, own free will. We nodded to each other, and exchanged smiles as we had just silently communicated, and I knew that my message had been received.

Another example of this phenomenon occurred during the exhibit's run at the Black Student center at the University of Missouri in Columbia. The building is a large new structure, with two large class rooms on the first floor. The exhibit was in the hallway right outside these classrooms, featuring a nice glazed wall with tinted glass, which illuminated the pieces nicely. Fortunately the glass was tinted so as not to damage the watercolors with direct ultraviolet light.

I asked the members of the host Community to see that someone would please check on the exhibit from time to time, just to make sure that everything was all right. They promised to do this on a regular basis for the run of the show which was set for two months. About half way through this time I received an email from the friend who had coordinated the effort to host the exhibit in Columbia, that she observed a student standing in front of one of the pieces and copying in her note book the quotation from the Writings that was mounted next to it! Needless to say it was extremely gratifying to learn that again, a communication had taken place, and that another wanted to record it.

These are only of the few experiences that are confirmations of the message being received by others through the medium of visual art. If this medium is such a powerful and silent communicator, then questions need to be asked about the created content that is to be communicated. If joyful art is created, its message will be joy, and the viewer will be given something positive that will nurture his soul. That special and very mystical bond that can be created between artist and spectator will have again communicated something to uplift the spirit and perhaps provoke an intellectual curiosity to further investigate the message just received.

Incidentally another interesting result of the exhibit in Columbia occurred when a reporter writing about the art in the Daily Tribune wrote the following:

In the lithographic and watercolor print "The Oneness of Mankind" Johnston portrays the large outline of a body filled with smaller human forms, tucked together like the pieces of a puzzle. Each of the tiny people is slightly different in size and color. Underneath the print is a quote from the writings of the Bahá'í Faith:

"Know ye not why We created you all from the same dust? That no one should exalt himself over the other. Ponder at all times in your hearts how ye were

created."

|